(click to enlarge those pictures)

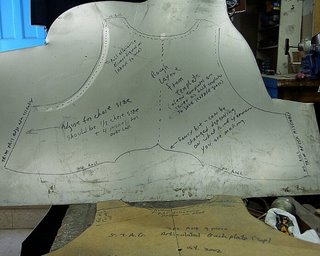

(click to enlarge those pictures)This backplate provided an inspiration to see if I could make a backplate as pretty as this one. It was made for a prince, or at least, a Knight of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem in the great armour shops of Milan sometime in the late 16th century. Stylistically, it makes my efforts look pretty amaturish! On the other hand, I think I have the shape of the steel figured out. In the bottom picture, I have just finished cleaning the piece of all its rust and crud from years of benign neglect. Mr. Stroud, the curator of the Palace Museum in Malta is explaining the results of a recent metalurgical survey on his precious armours. The job took about three hours, and a labour of love. It was not particularly dirty after all, and I did not have to go into the chiseled decoration at all. Thank goodness for that! I was not looking forward to two weeks with dental picks!

The piece is remarkable in that the edges are not just rolled, but roped as well, and there are some embossed parts...that is parts that are raised up and away from the metal....the roped decorative strip an inch or so from the edge of the arm holes, and the embossed medallions at the back. There were several of these backplates there, all had the medallions and embossed lines which seemed to be standard. The roping and engraving on the medalions are all added on later, and of course are all different. The patterns on the three big wide stripes are made with hammer and punches in a process called (paradoxically enough) raising. The pattern is fairly common, the curators call it "pots and pans". The metal was probably backed up with lead during the raising process, and neillo was burned into the depressions. Special bricks were used to polish the surface after that. The broken rivets near the bottom are all that remains of the steel buckle mounts. I have no idea how they managed to raise the pattern near the bottom....I can only think that the roping was pushed up after the decoration was all done. I like it! No doubt in a few years, I will be doing work just as good. (sure.....I believe that!)